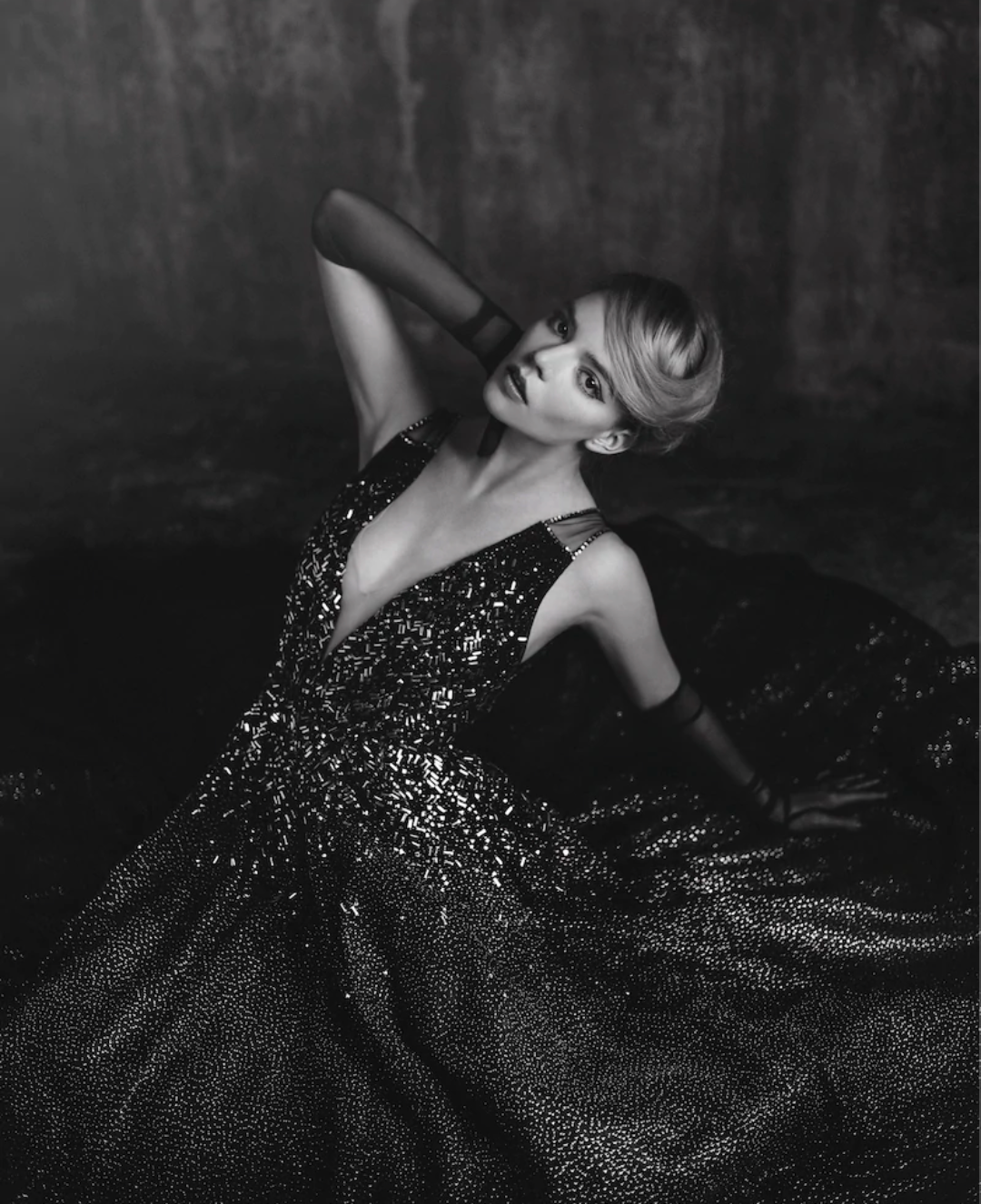

Taking a stroll down the SS22 catwalk via Nina Ricci, Lanvin, Saint Laurent, Maisie Wilen, Batsheva and Yohji Yamamoto, you might be wondering – exactly where did this new-found penchant for the opera glove come from? Experiencing a resurgence via the arms of literally everyone (from Alexa Demie, Kim Kardashian and Lizzo to Rihanna and Beyoncé), one thing’s for sure — the opera glove has just as much star power as its dazzling sartorial entourage. However, this is certainly no new fad. Even before the golden era of Hollywood cinema, with Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn and Sophia Loren all showcasing ladylike iterations of the design on the silver screen, the opera glove has been a long-standing relic of high fashion. So, why do people wear opera gloves? Well, it’s the result of lots of historical and social developments. With the first known inception of accessory dating back to the 17th century, the opera gloves' purpose is as ever-changing as the aforementioned list of celebrities and their countless pairs. Used to communicate many things, including wealth, royal status, good taste and great manners, it’s a design that’s had the luxury world in the palm of its (very tactile) hand for centuries. So, at the risk of sounding like a sartorial Socrates, here are our philosophical findings to the big question: ‘What is the purpose of the almighty opera glove?’

What Was The Purpose Of Opera Gloves, Originally?

Let’s rewind back a little bit. And by a little bit, we mean a lot. Hello, Victorian era. Following the Regency and Napoleonic glove craze (with Napoleon himself reportedly owning 240 pairs), it was during this time that the opera glove began to really boom. Spotted on the hands of each and every, the Victorians really loved their gloves – and not just because they looked nice. Fixated by etiquette rules, daily Victorian life would be dictated by a long list of social dos-and-don'ts. Any guesses for one very popular apparel rule? That’s right — wearing gloves. Specifically, Victorians were commanded to ‘never go out without,’ so it would be near impossible to spot anyone without a pair.

The glove craze communicated many things about its wearer to the passing world. For wealthy women, wearing expensive styles would indicate they didn’t need to use their hands for laborious work. It also told people that they could afford such luxuries, which had previously been exclusive to royalty. To avoid social faux pas (and to keep up with the latest trend), the working class would adapt the style to fit their budget – opting for cheaper pairs that would hide their roughened hands. Day and night styles would be interchanged accordingly, and as a result the Victorians decided it was officially ‘rude’ to flash your forearm to the world.

In a chain reaction to the above, Victorians further decided that one should always attend formal social affairs with a plus two — a pair of opera gloves. As the name would suggest, it gained traction during the Victorian heyday of the grand opera. However, the opera glove wouldn’t be exclusively restrained to a life of Ludwig van Beethoven and Henry Purcell. From the theatre to weddings, it would be considered an insult to arrive at any formal event without a pair.

To keep up with the daily demand, Victorian glove-wearers favoured the mousquetaire style, which is defined by its button openings at the wrist – allowing its wearer to slip a hand out without having to take the entire garment off. Gloves would typically be tailored, with practical leather and suede daytime styles being swapped by nightfall for evening-appropriate silk and satin pairs.

What Else Did People Wear To The Opera?

So, what else would one wear to the opera? Why, we’re so glad you asked. In short: plenty. But you didn’t come here for the short answer, did you? This is Cornelia James and you know we take our sartorial findings very seriously, so here’s the long of it…

Firstly, gentlemen would often arrive wearing the opera hat, which is essentially a collapsible version of the top hat. Invented by London hatter Thomas Francis Dollman, it was a popular component to the white tie dress code – mainly due to its formal appearance and ergonomic design. The top of the hat would fold inwards to form a flat top, which made it easy to store in the cloakroom or beneath a theatre seat. You know, so people could still see what was going on when they sat behind a well-dressed opera-goer. Typically composed from the finest of black silks, you’ll be surprised to learn that the opera hat quickly became indicative of social status. (Not.)

Ladies who frequented the opera would also arrive in their own version of the opera hat, known as the opera bonnet. Despite the fact that wearing a hat indoors would generally be frowned upon during Victorian and Edwardian times, women would sometimes feel too exposed in the expansive environment of the opera, and would prefer to cover their heads. Therefore, the opera bonnet became a popular piece. A hooded style that was usually crafted from velvet or some other form of fancy fabrication, the opera bonnet would typically be trimmed with flowers or some light feathers.

Another popular design was the opera cloak. With iterations for both men and women, the gentleman would style his opera cloak over the top of a black tuxedo or white tie and tails. Ideal for protecting one’s very best attire from Britain's gloriously sunny weather (at Cornelia James, we do sarcasm alongside sartorial history lessons), the cloak would be lined with the finest materials and fastened with a unique clasp around the neck, allowing it to drape the wearer with floor-length folds of dramatic fabric. For gentlewomen, the opera cloak was much more of an opulent centrepiece. Embroidered or adorned, it often boasted a high neckline with a ruffle surrounding the face.

Another piece of warm-weather formalwear (see above disclaimer), the opera coat succeeded the opera cloak, as the formative style fell out of women’s fashion in the late 1800’s. Made from luxurious fabric and landing at a floor length, it absorbed many of the same style characteristics of the opera cloak. However, it also had some new details, such as a trimmed fur collar and giant shoulder pads to exaggerate the form.

Women were also encouraged to dress as elaborately as their pockets would allow, with opera rules detailing expectations such as: ‘The hair should be dressed as for a large evening party, and artificial flowers, jewels, feathers, ribbons or any style of head-dress peculiar to the fashion may be worn.’

How Have Opera Gloves Been Repurposed?

Whether you’re a frequent attendee at Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia or a midnight sorceress at your very favourite highbrow (or not so) bar, opera gloves are one sure-fire way to bring some antique marvel and magic to the modern day. With long gloves fashion punctuating the runway, red carpet and glossy editorials across the globe, its star power is just as undeniable as it was centuries ago. However, the design has also experienced a contemporary evolution. So, from modern leather opera gloves to traditional silk and satin styles, you might be asking yourself: why do women wear opera gloves today? Well, there are many likely reasons — and all of them point back to the fact that they look, well, ridiculously great.

With the presence of the opera glove in the A-list landscape – including their key role in many musical video visuals, from Ariana Grande and Adele to Dua Lipa and Olivia Rodrigo – the influence of the opera glove is beginning to trickle into our own reality once again. Also playing a key part in many SS22 collections, those with an eagle-eye for fashion have already attached new-found status to the opera glove. Ironically, it doesn’t seem that far removed from its Victorian aesthetic message. Indicative of good taste and composed styling, the opera glove continues to define the most luxurious corners of the world.

The modern elixir to your formalwear woes, those looking to emulate the contemporary trend won’t need to look far for an accessible taste of the fast lane. Clue: we have a whole opera gloves collection right here at Cornelia James. You’re welcome.